Ebenhaëzer 1904

A. S. B. Ebenhaëzer (Ebenezer in English) was

registered in 1904 having been built in the Croles shipyard in IJlst, (just

outside Sneek, Friesland) in the Netherlands.

Now an auxiliary sailing barge

she is a 63ft (inc. fixed bow sprit) gaff sloop rigged, sailing barge

(tjalk). She was registered for

‘Binnenvaart’, or inland trade. She was purchased by her current owners as

Geertruida in 1992 in Friesland, though she had also previously been re-named Butsekop

and Vrouwe Harmke. Her documentation was located in 2002 and it was

discovered that Geertruida was not her original/correct name. Consequently, she was ceremoniously

'de-named' to her true name of Ebenhaëzer (Ebenezer), by which she had been

known for most of her life. It's stated

that her use was transporting bulk cargo, mainly in Friesland (a northern

province of Holland).

Around 1900 there were as many as thirty different types of tjalken in the Netherlands, all of them being built and equipped for very specific kinds of transport routes and waterways. “Ebenhaëzer” is a specimen of a Frisian tjalk of the largest category: 15 to 20 meters long and used for the transport of bulk cargo. The smaller type was 10-12 meters long and primarily used for the transport of mixed cargo in small quantities on a regular basis, mostly once a week, between the villages and market towns.

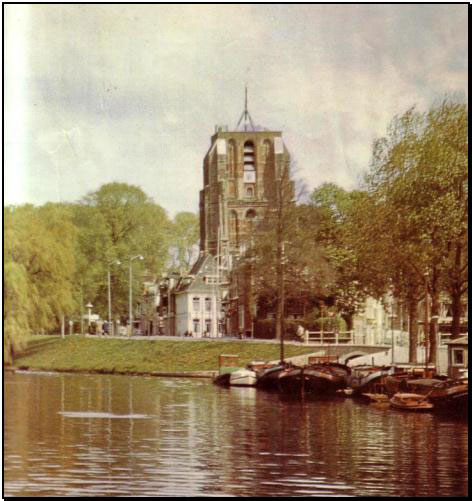

Map Showing the

Region in which Ebenhaëzer Operated and

was Built.

It also Shows Leeuwarden, where her Current

Owner Purchased Her

Her current owner

first viewed her in 1992 in Leeuwarden, the capital town of Friesland. She was then sailed via Belgium & France

to berth on the Thames in early 1993. Several years later, she was sailed on to Ireland from the East

coast of England starting from Maldon on the River Blackwater (Essex), via the

Thames, Kennet & Avon Canal, River Avon, Bristol Channel, Welsh coast

(Milford Haven), St Georges Channel, Dunmore East (Waterford – SE Coast of

Ireland), Barrow, Grand Canal, arriving on the River Shannon in 2000, where she

is currently based.

|

Barge Name: |

Ebenhaëzer |

|

Hull Construction: |

Riveted Lomar Iron (Swedish Iron) |

|

Engine: |

DAF 575, 6 Cylinder, 125 Horse Power |

|

Registration Number: |

S 639N |

|

Locality of Registration: |

Sneek, Friesland |

|

Year: |

1904 |

|

Shipbuilder: |

Croles Shipyard, in IJlst, Friesland, NL |

|

Rig: |

Gaff Sloop |

|

Thames Tonnage: |

50 Tonnes |

|

Cargo: |

Bulk Cargo in Rural Regions: Manure, Mould, Peat, Coal, Hay, Straw, Reeds, Potatoes, Sugar

Beet, Building Materials etc |

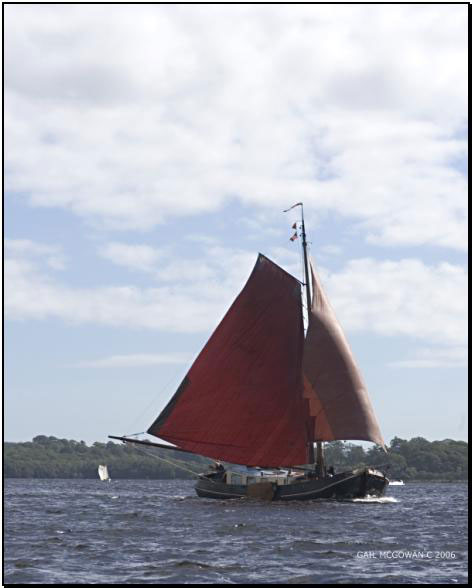

Ebenhaëzer Sailing on Lough Erne (Northern

Ireland) at Classic Boat Regatta 2006 (S. Carson)

Ebenhaëzer

off Whitstable in Kent, England during

the Swale Barge Match in1999

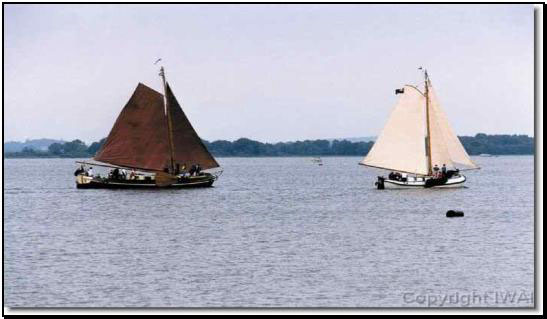

The following year 2000, in company with Lemsteraak Schollevaer

outside Lough Ree

Photo: Edward/Pamela Burrell

Yacht

Club on, River Shannon,, Ireland

Ownership

|

A.B. Meijer |

1904 - 19?? |

Ebenhaëzer |

Lutkewierum |

|

Doen Fennema |

19?? - 1918 |

Ebenhaëzer |

Scharnegoutum |

|

Wieberen and Antje Paauw |

1918 - 1950 |

Ebenhaëzer |

Makkinga |

|

Pieter Zuidemea |

1950 - 1964 |

Ebenhaëzer |

Leeuwarden |

|

Jan Geert de Jong |

1964 - 1985 |

Butsekop |

Gorredijk |

|

Dirk Piersma |

1985 - 1988 |

Vrouwe Harmke |

Dokkum |

|

Geiko Reder |

1988 - 1993 |

Geertruida |

Blijham, Groningen |

|

Rachel Hanna (Leech) |

1993 |

Ebenhaëzer |

London (UK), Athlone (IRL) |

Ebenhaëzer

Approaching Big Ben & Houses of Parliament, London in 1999

The ship was registered in 1904 as “Ebenhaëzer” (Ebenezer

in English) . The name Ebenhaëzer

(meaning “Stone of Help”) is of hebrew origin and was derived from the Holy

Bible, paying tribute to a stone which Samuel used as beacon between Mispa and

Sen, in remembrance of the defeat they had over the Philistines.

"Ebenhaëzer" can be translated as "the Lord has helped us thus

far" or “the Lord has helped us up to here” (1 Samuel 7:12). In

Ebenhaëzer’s early days, the local Dutch Reformed Mission Church was the

cornerstone of the community.

Centuries later, it was interpreted that Ebenezer Scrooge in Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol” was not living up to the true definition of his name (the true potential his Creator initially intended), until he received supernatural intervention that caused him to have a change of heart and, thus, enabled him to be a financial “Stone of Help” to those around him.

Ebenezer

Scrooge

She retained this name until 1964 when she was renamed “Butsekop”, meaning “Sperm whale” in Frisian, due to the whale’s blunt head. She was again re-named (dutch for lady) Harmke and also Geertruida in 1985 & 1988 respectively, after family members. Her name was restored to her by her current owners.

The Inland Traders

The Binnenvaart (Inland Trader) Skipper & His Family

Ebenhaëzer was registered for binnenvaart in 1904. At the turn of the century there was a bewildering range of binnenvaart (inland trade) ship types. However, very simply put, the vast majority of the true inland freight ships sprang from one of two very old hull forms. These were the tjalk and the aak. Ebenhaëzer is a tjalk. By the end of the nineteenth century, the tjalk was the most common of all the Dutch binnenvaart ships. The change from wooden to iron construction saw little appreciable change in the tjalk form. The use of metal rolling techniques allowed a curved bilge to be introduced, replacing the harder chine previously seen in wooden construction, but otherwise the design remained unaltered. Although the tjalk shares many features with other binnenvaart ships, they can be recognized primarily by their distinctive hull form. Tjalken were built to carry cargo, as much cargo as possible and so they are recognizable by the rectangular shape of the hull. The curved "voorsteven" (stem), which also leads to them sometimes being referred to as "Kromstevens", or bent stems and the inward turning "boeisel" (the upper portion of the hull), are all indicative of the tjalk hull form. A heavy iron band, the "berghout", is carried all around the hull for strength and to act as a rubbing strake. The bottom is flat with no keel or keelson and has a noticeably rounded bilge. The wooden rudder is very large and mounted on the stern post on conventional gudgeons and pintles.

All tjalken and aken were originally fitted with a zwaard

(lee board) on each side. These were of

wooden construction and had a subtle airfoil form. They were fan shaped, distinguishing them easily from the deep

water craft whose zwaarden were long and thin.

The sailing rig consisted of a loose footed gaff grootzeil (main

sail) on a heavy boom, a small fok (staysail), self tacking on a horse

just forward of the mast and one or more kluivers (jibs), carried on a kluiverboom

(bowsprit). The use of ketch rig and

top sails originally occurred only on the larger tjalken engaged in the coastal

trade and the larger Rijnaken. The

typical length was between 15 to 25 metres and the weight from 20 to 150

tons. The length to beam ratio was

normally in the order of 4-5 to1.

Zwaard (Lee Board) Lee Board Functionality

During the nineteenth century, the vast majority of binnenvaart tjalk skippers owned their own ships and arranged their own cargo. They were both merchants and sailors and well respected in their home town. The cargo these merchant-sailors carried was diverse and reflected in the evolution of the ships that carried it. Peat, hay, reeds, potatoes, cheese, sugar beet, manure, all generated differing techniques of carriage and slightly different ships. By the end of the century the growth of "big business" meant many skippers were being forced to relinquish their role as merchants and to put this function in the hands of a middle-man. The skippers resented this departure from their traditional freedom and as the power of the land based merchants grew they saw their own influence waning. This continued in spite of attempts by the skippers to avoid exploitation and the effects are still felt by today’s binnenvaart fleet.

In the latter part of the nineteenth century, canals and rivers still formed the backbone of the Netherlands inland transport system. The railways were spreading, but theirs was still a secondary role. Wherever the lines crossed a canal, or small river that had recognized navigational use, it was necessary to construct a movable bridge to allow free flow of water traffic. When a railway line crossed a wide waterway, such as the Rhine, it was necessary to construct a fixed bridge. A lifting, or swing bridge, would have been technically difficult, as well as expensive to construct. In these cases, the railway companies paid for those ships using the waterway and lacking a mast lowering facility, to have their ships converted. The men who looked after the thousands of bridges, road and rail and also the sluices, played an important part in keeping the trade moving. The skippers paid for every bridge, or sluice, that had to be opened. This provided the funds to maintain the canal system. The general rule was, that a bridge or sluice "watcher", as they were called, would be on duty from one hour before sunrise, to one hour after. It was not forbidden to use the canals at night, but the skipper had to stop sometime and generally night travelling was not done. When it was attempted, perhaps as a skipper wanted to get an early start, the rule was that it would cost ten cents, this was four times greater than the day fee. Even then there was no guarantee that a man would get out of bed for ten cents! The bridges and sluices were all manually operated and this could mean a long hard day. However, the watcher was generally well paid and a house normally went with the job. Often a cafe would grow up at these sites and the skippers would try to reach these points before nightfall. Here they could meet friends, exchange news and stories and, if the wind was foul, arrange for a man and horse to tow him on his way. This job was often undertaken by the farmers who owned the land beside the canal. They would farm with "one eye on the canal" and then provide a horse to tow the barge through their "territory". If the skipper was lucky he would soon find another tow, but if not, it was up to him and his family to provide the power. It was that or wait for the wind. Although the work was hard, so too were most occupations for the non city dweller. Although some merchants in the cities owned several ships and employed regular crews, most ships were owned by their skipper and operated from the towns and villages of the countryside. At the end of the nineteenth century, people did not, by and large, travel very far outside their home town. Those that did travel were looked up to and engendered with a certain mystique. In Drente, for example, the skippers of the small barges that carried turf, had a higher status than a farmer, but the skippers who sailed the bigger craft, across the Zuiderzee to Amsterdam, were seen as real seamen and looked up to even further. They were seen as real gentlemen and addressed as "Sir".

Lemsteraak

“Schollevaer” & Tjalk “Ebenhaëzer”, Late for Last Lock. R. Shannon 2006

The Zuiderzee was a physical and social barrier to the people who lived to the east of it. To the skippers it represented a real challenge and a whole new set of techniques and equipment were needed to cross it safely. The water authorities provided warehouses on its shores, where the skippers could store the heavier sails, hatch clothes and ground tackle, needed for this "overseas" trip. When they had brought their ships successfully to Amsterdam, each group of skippers, from similar areas and towns, had their own meeting places, where they felt secure. The Drentse skippers stayed in the "Haarlemmerstraat" and those from Hoogeveen at the cafe "De Ramskooi". On their return to the eastern shores of the Zuiderzee, they would exchange their heavy sea going gear once more and return to their families. They made a habit of staying away no longer than three weeks and would not sail at all at Christmas and Easter. They were a religious people anyway, but the skippers in particular were rather pragmatically more so, they experienced the forces of nature regularly and were aware of their own vulnerability.

The skipper of a tjalk or aak, was nearly always himself the son of a skipper, who had, in turn, married a skipper's daughter. This intense family involvement in the binnenvaart produced strong ties and loyalties. In times of hardship, or personal difficulties, these people would "close ranks" to protect their own. These were an astute group of people, as good at conducting business as at sailing ships. They were aware of the advantages that a good education could bring and although school was not yet compulsory, often went to great lengths to ensure that their children attended school as regularly as possible. This meant that a skipper's son, at the age of fifteen or sixteen, would already have a good academic, commercial and practical background. A son would learn his trade from his father, working as a deck hand on the family craft until he was able enough to be employed on another ship. When he had saved sufficient funds, he could approach his parents and some of his many relatives for loans to enable him to buy his own ship. A ship that was for sale would often discretely display a handful of twisted straw pushed through the hook at the outboard end of the tiller. Another skipper would know what this sign meant but most other observers would remain in ignorance. The inboard end of the tiller might proudly display a handgrip in the form of a barrel, this traditionally meant that the ship was paid for and the sole property of the skipper. The young owner was not seen as a "real" skipper however, until he employed a knecht (deck hand). When he got married, his wife would live on his ship with him and they would raise a family on board together. The skipper's wife was often mother to all on board, the skipper, the deck hand and the children. She would cook for all, in the tiny confines of the roef or paviljoen (living space), all the time listening for the sound of a child falling overboard, or the skipper and hand arguing. It was her job to mediate and calm things down with a cup of coffee. Sometimes, the skipper, his family and the deck hand, would all live together, but often the hand was expected to make a bed for himself in the forecastle. In the larger ships he would even have his own stove. Generally though, living was cramped, a tjalk made its money from carrying cargo, not people.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the Dutch binnenvaart fleet expanded more quickly than any other form of maritime activity. Dutch binnenvaart skippers sailed to all accessible parts of Europe. It may justly be said that through their hard work and skill they formed the backbone of the Dutch economy.

Research

Identification of Dutch

Barges

Meetbrief

The "meetbrief" is the registration book belonging to an individual vessel. Each ship was given a unique number on initial registration and this number, which is also the "meetbrief nummer" stayed with the ship for life. On older ships, the date of initial registration as given in the meetbrief is not necessarily the same as the launching date. Certainly many ships trading in the latter part of the nineteenth century were not registered on the "modern" system until the later part of the 1920’s.

For registration purposes, the 11 provinces making up the Netherlands at the beginning of this century were split into three "metingsdistricts". Rotterdam, signified by the letter R, covered the provinces, of Limburg, Noord Brabant, Zeeland and that part of Zuid-Holland below a line joining the cities of Leiden and Utrecht. Amsterdam, signified by the letter A, covered the areas of Zuid-Holland above a line joining the cities of Leiden and Utrecht, and the provinces of Noord-Holland, Utrecht and Gelderland. Groningen, signified by the letter G, covered the provinces of Groningen, Friesland, Drente and Overijsel.

A vessel that had permanent residence, or intended to trade in any of these areas, was measured and registered by the "ijkantoor", the local weights and measures department. In each of the three metingsdistricts there were many separate "kadasters", or registration offices situated in the main towns of the region. These offices would handle the three separate registration and measuring procedures.

1) IJKMERK

2) TEBOEKSTELLINGNUMMER

3) METINGSMERK

1) IJkmerk

The "ijker" was the official weights and measures officer, he was responsible for calculating the acceptable loading capacity of a ship trading in a pre-defined area. When the calculations were complete he also issued a number, the "ijkmerk", which was stamped into the ship’s side. The location of this number is detailed very precisely in the meetbrief (paragraph 28), it appears twice on each side of the ship at bow and stern. A horizontal line drawn between the two numbers corresponds with the maximum loaded waterline in fresh water. Every time a ship moved into a different trading area it was required to be re-measured. The maximum allowable waterline in sheltered canals was markedly different to that deemed safe in exposed or open waters.

2)

Teboekstellingnummer

When the measuring and marking was complete, they would issue another unique number, signifying when and where the registration was done. This number, the "teboekstellingnummer", is in four parts. Eg. 210 B AMST 1927. In this example the numbers simply mean that it was the 210th ship registered in that year. The B is very important. It means Binnenvaart, or inland trade. A ship trading on coastal routes or in the Baltic for example, had to be strongly built to a higher specification and these ships would have a Z for Zeevaart as part of their teboekstellingnummer. AMST of course means the registration office was in Amsterdam. These letters generally take the form of the first four or so letters of the town in question. ZWOL for Zwolle, APPING for Appingedam, DEV for Deventer, LEID for Leiden, UTR for Utrecht, ARNH for Arnhem, etc. The last four numbers signify the year the number was issued. The location of the teboekstellingnummer is given in the meetbrief (above).

3)

Metingsmerk

After measurement the meetbrief was issued. At the same time a number was assigned to the vessel. This became the meetbriefnummer and also the ship number, the "metingsmerk", or "brandmerk". It consisted of the signifying letter of the area, the letter "N" denoting Netherlands and a unique number. This number appeared in the form of a brass plate riveted to the ship’s side. However time showed that these plates tended to drop off due to wear and tear and later ships had the number stamped into the fabric of the hull and also into the superstructure. The location of the number is given in the meetbrief.

Flag of Friesland

Officially, the registration office had to be notified of any change of trading area; change of ownership; change of name of ship; or any substantial alteration to the ship such as lengthening, conversion to motor, or change of existing motor. The ship could then be re-measured if appropriate and the meetbrief altered accordingly. Every change in the meetbrief, which in any case had to be renewed every fifteen years, cost hard earned money. The more prosperous skippers and those owners with large fleets tended to be scrupulous about such things, but the thousands of one-ship-skippers couldn’t afford to be so precise, unfortunately leading to gaps in documentation and problems for the researcher. However, if it is possible to locate the metingsnummer, or better still a teboekstellingnummer, by contacting the "Scheepskadaster" in the relevant town it is often possible to unearth more of the history of the ship.

Ebenhaëzer Approaching Tower Bridge, London

The documentation sourced on Ebenhaëzer was partially in

old Dutch and it was difficult to translate.

There is a collection of documents from various stages and eventually in

2005, a Dutch friend of the owner of the Lemsteraak “Schollevaer” (also based

in Ireland), was to come sailing on Ebenhaëzer on Lough Ree. He had been Secretary of the SSRP (Stichting

Stamboek Ronde en Platbodemjachten) which is the Corporation/Foundation for the

Documentation of Round and Flat Bottom Yachts, in the Netherlands and has

considerable knowledge of Dutch vessels and sailing of same. He was to uncover the ownership of

Ebenhaëzer, and in doing so, has been liaising with the four owners of the ship

in the last 43 years.

As mentioned above, the first identifying number of a ship was the "meetbrief" number, given when she was initially measured. The record number of this measurement, being S 639 N in Ebenhaëzer’s case. However, much confusion was to follow, as the length overall was stated in later documentation at 9ft longer against her actual length! It was therefore initially feared that the documentation was incorrect.

For most of the first half of the 1900s Wieberen and Antje Paauw were declared to be the owners of the Dutch iron ship with deckhouse “Ebenhaëzer”, sailing the inland waterways. Measurement, according to her meetbrief, was recorded in the register of the District of Sneek with the number 639 N, 39,792 tons. Both of these markings are to be found on the hull (meetbrief number and tonnage). According to the documentation, the measurement took place in Sneek in 1905.

In 1938 the then current owner appears to have had her extended to 19,81 m. in Lemmer at the shipyard of the De Boer brothers. There are no first hand documents about the extension but Mr Vos (researcher) contacted the supervisor of the small museum in Lemmer where the shipyard records of the De Boer brothers are kept. She advised him that she had records of this from 1938.

In 1938 Mr Pauw appears to have had her extended to 19,81 meters, probably in Lemmer at the shipyard of the de Boer brothers. Mr Vos contacted the supervisor of the small museum in Lemmer, where the records of this shipyard are kept, and went through the period 1930-1940, but he could not find any indication of this extension.

Confirmation is to be found in a later document, being the record of the measurement in 1938. It states that former measurements took place in Sneek, on the 8th of March 1905, registration number 639 [S 639 N) and in Meppel on the 11Th of February 1932, number 589 [MP 589 N], which is also to be found on the hull. Whether she was at her longer or shorter length at the 1932 measuring, is as yet unclear, as those particular registers were sent to a museum in Rotterdam and have not yet been traced (in other words it will confirm if the hull extension took place between 1932-38). This information will confirm whether or not in 1938 she was 19,81m long and had a deadweight capacity of 49,686 tons. There is also a “metingsmerk” [G 4955 N]. This was the number given after the re-measuring in Lemmer in August 1938. The office where the measuring register was kept, was in Groningen (G), while the measurement took place in Lemmer, presumably following extension of the hull.

Further documentation shows a request for “teboekstelling” in 1954 by Mr Pieter Zuidema, the new owner of that time. She was still 49,686 tons by then and the “teboekstellingsnumber” was 387, [387 B Leeuw 1954], which is to be found on port stern gunwale. She was still registered for inland trade (Binnenvaart), at this point.

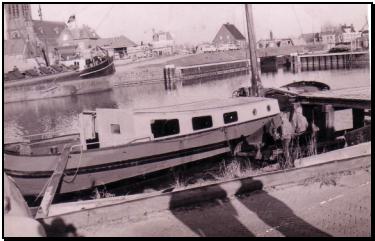

The collective documents confirm that during the war years (1938) “Ebenhaëzer” was extended by three metres. Now the vessel has been shortened again, so it is concluded that she must have been shortened to her original length later than 1964 because in the documentation of that year, the then owner Mr De Jong declared that she still measured 49,686 tons when he bought her that year. There is also a picture of her in 1962 at her longer length below (provided by J de Jong). She is the long orange and black vessel, then owned by Mr Pieter Zuidema. His parents lived in the tjalk alongside “Ebenhaëzer”. The picture was used as a local postcard. It is evident that the ship is still 19.8m LOA. Mr De Jong purchased her having viewed her in the above setting.

Ebenhaëzer Moored at Leeuwarden between

1962-1964

History

History of Ebenhaëzer

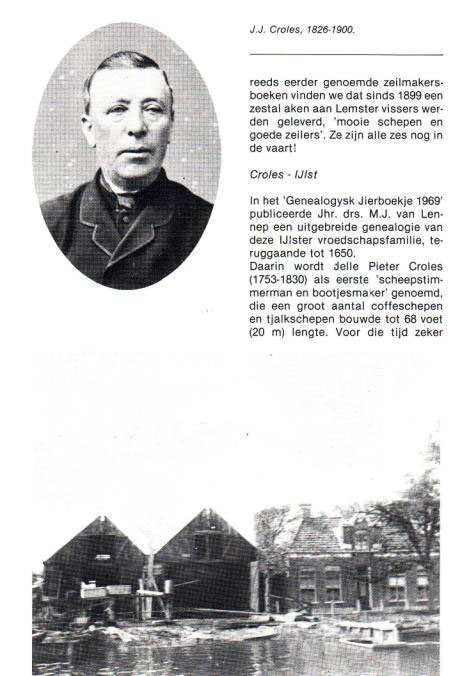

Ebenhaëzer was purchased by her current owner under the name of Geertruida, having been built by Croles of IJlst (near Sneek, Friesland) in 1904. Below is a picture of the Croles shipyard in IJlst and of J.J. Croles who was the owner of the shipyard in until his death in 1900. Co-incidentally, it turned out that the shipyard had been located no more than a 5 minutes drive from our researcher’s home (Mr Tom Vos). The yard was discontinued before WW II. In the Maritime Museum he learned that Mr J.J. Croles Jnr, who was the intended successor to the shipbuilder who had died in 1900, had no ambition for shipbuilding; he qualified as a lawyer in 1898 and later became a politician, never having had anything to do with the ship yard. The widow continued the business after 1900 with help of a foreman as this was the only way of earning a living for herself. She died in 1918 and the yard was sold on, though it ceased business somewhat later – possibly in the 1930s.

Croles Shipyard in IJlst. Above is JJ Croles, owner of the shipyard who died shortly before start of

construction (his widow continued to run the shipyard)

The barge originally was solely a sailing vessel. A.B. Meijer, Doen Fennema, and Wieberen

& Antje Paauw would have used her for the transport of bulk cargo, in a

completely rural society: manure,

mould, peat, coal, hay, straw, reed, potatoes, sugar beet, building material

etc. Mainly, she would have operated in

Friesland. In the early 1900s in

Friesland there were hardly any paved roads.

Nearly all traffic went over water, along the canals and lakes, sailing,

rowing, poling or towing along the banks. Many canals and all the lakes

of course, were so wide that sailing was the main means of propulsion

used.

Before the war years (1938 or sooner), Wiberen Paauw had her lengthened by 3 metres. Those were years of economical depression – most people were very poor, freightages were low and probably it was done to enable extra capacity per delivery, to make it more financially viable. In 1941 the registration as a cargo vessel ended, probably because Wieberen Paauw had died. Antje (his sister) continued to live on the barge until 1950.

In 1950 Mr Pieter Zuidema bought her. During his ownership, he de-rigged her and fitted an engine. He re-registered and used the barge for cargo transport until 1964. However, it is believed that she may have been lying idle for one or two of these years in Leeuwarden by 1964. Mr Zuidema moved (possibly retired) to The Hague in 1964. It was from Leeuwarden in 1964 that that Mr Jan de Jong purchased the ship and from that point, she has been used for pleasure, like many other similar barges in the Netherlands.

Ebenhaëzer in Leeuwarden, 1962

In the picture above, Ebenhaëzer is the third vessel from the left. She had been de-rigged for a period at that point (she is the one with the dark stern and a small dinghy on her starboard side). She was then owned by Mr Pieter Zuidema and was at her longer length. This picture was used as an illustration on a calendar at the time (Photo: Provided by Jan de Jong).

Mr De Jong advises that Mr Zuidema had installed a Bernhard engine of 12 hp which was still in her when Mr De Jong purchased her in 1964. Similarly to the Bolinder single stroke engines used by Canal Boats (barges) in Ireland, it was started by flywheel. The Bernhard was primed with petrol. When running the fuel was changed to paraffin oil. It was not possible to put it into reverse directly: the engine was paused and started again after turning the clutch. As the engine had been placed close to the after bulkhead of the hold, this operation took considerable effort, so that moving the barge was not very convenient and required planning. Mr De Jong was also much taller than Mr Zuidema so he had to kneel to spin the flywheel. As a result, he replaced the Bernhard with a Ford A car engine and later with a Mercedes OM 636 diesel.

He set about re-shortening and re-rigging Ebenhaëzer, which he renamed to Butsekop and later set about building her a new ‘deckhouse’. Initially, when the barge had been restored to her former length in Terhorne, he brought her home to Gorredijk and removed the deckhouse himself. He constructed the seats and the platform under the tiller (cockpit) using steel plates. He had plenty at his disposal as a manager of a Milk Can Factory, for which they were the basic material. Those plates were only 1.5 mm thick but were covered in teak (this remains unchanged).

Re-shortened & Re-rigged 1964 1964 Painted Green

He also built a temporary wooden deckhouse with more headroom to create more space in the “kuip” , until it was replaced by the current steel structure. The picture below shows Ebenhaëzer in Stavoren, a small town in the South West of Friesland. She is at the Van der Werff shipyard where the superstructure work was done. The yard was established in 1800. Mr De Jong consulted a professional nautical architect to design the cabin (these 3 pictures are from the log of J. de Jong).

1965,Current

Steel Cabin Construction

In 1985 Mr De Jong sold “Ebenhaëzer”, then “Butsekop”, to Mr Dirk Piersma in Dokkum. Mr Piersma maintained the name “Butsekop” for a few years and then changed it into “Vrouwe Harmke” .

Mr Piersma knew a fellow townsman in the wastepaper business who owned a truck and was selling his business, having retired early in the 1980s. Mr Piersma started negotiation about the truck’s disused DAF 575 engine (Ebenhaëzer’s current engine) during a cold spell in winter 1985/’86 and started negotiation on the engine in a temperature of about minus 10°C! Some fuel and a loaded battery were organised and when turning the key the engine started coughing, banging and expelling black smoke, but then it ran smoothly and that gave Mr Piersma sufficient trust in it, so he bought and replaced the Mercedes with it.

Moored in the Centre of Dokkum during the 11 City Skating Race in Winter 1987 (Photo: D Piersma)

The above picture during Mr Piersma’s ownership, is of Ebenhaëzer moored in the centre of Dokkum during the “11-cities skating race” in February 1987. It is unique in that it is the most famous outdoor skating event in the world. They call at every city of Friesland, being 11 all together, during a skating match (and tour for amateurs) of 220 kilometres. It can only be organised when winter is very severe and the ice is thick enough to carry 20,000 people, which seldom occurs, since the last ten or twenty years. Notice the crowd of visitors on both sides of the canal. The five photos below are also provided from the log of Mr Piersma.

1980

Sailing on a Frisian Lake

Foredeck and

Zetteboord 1985

1985

Illuminated on the Canal in Centre of Dokkum

She was still named “Vrouwe Harmke” in 1988 when sold to Mr Geiko Reder who re-named her Geertruida, after a family member. A copy of this contract of sale was obtained and added to the collection of documents. Mr Reder sold her on to her current owner, Rachel Hanna (then Leech) 4 years later in 1992, via a broker, having been viewed in Leeuwarden and she is still fondly referred to as “Gertie”, short for Geertruida. In fact the sale was not finally completed until early 1993, when she travelled by water to the Thames (via Netherlands, Belgium, France and across the English Channel up the Thames, where she was to be based for some years.

The ship then cruised to Ireland in 2000. She travelled back from the East coast of England where she was having works completed (in Faversham, Kent). She cast-off Maldon on the River Blackwater (Essex), via the Thames, Kennet & Avon Canal, River Avon, Bristol Channel, Welsh coast (Milford Haven), St Georges Channel, Dunmore East (Waterford – SE Coast of Ireland), River Barrow, Grand Canal and finally to her owner’s family home at Abbey House, Athlone, on the River Shannon where she is now based.

During her

current ownership she's been used for residential, cruising and sailing

purposes (including occasional mixed/classic fleet racing). She cruised the British waterways for many

years (costal, canals & rivers).

She also attended some of the traditional sail events such as Thames

Sailing Barge Matches on the Thames Estuary (normally raced on Kentish and

Essex coastlines). One of these

events, the Swale Match, also has classes for fishing Smacks, Bawleys and other

traditional craft - around the Isle of Sheppey, in which she raced on a few

occasions.

She has also

cruised all of the various navigable Irish and Northern Irish inland waterways

(canals, rivers, lakes), Shannon & Suir estuaries and Dublin

coastline. During some of her 2005

travels, she visited the Tall Ships Race in Waterford, taking the opportunity

to cruise the 3.

Classic Boat

Regatta, Lough Erne, Northern Ireland (Shannon One Design Fleet Behind). Photo: Stephen Carson

Dressed Overall

Before Oxford Cambridge Boat Race, Putney 1998

Gallery

Click the

Camera to View Photo Galleries

(CURRENTLY

UNDER RE-CONSTRUCTION)

Guestbook

Click the Book

to Sign the Guestbook

Photo: Stephen Carson

Links

Photo: Reggie

Goodbody

Acknowledgements

In particular to Tom Vos who painstakingly completed most

of the research,

Also to, David Evershed

Jan de Jong

Dirk Piersma

Geiko Reder

Ian Irving

Geoff Binns

Selina Bayly

Reggie Goodbody

Edward/Pamela Burrell

Photo: Selina Bayly